Blog

Technical deep-dives on AI, machine learning, and software engineering.

Technical deep-dives on AI, machine learning, and software engineering.

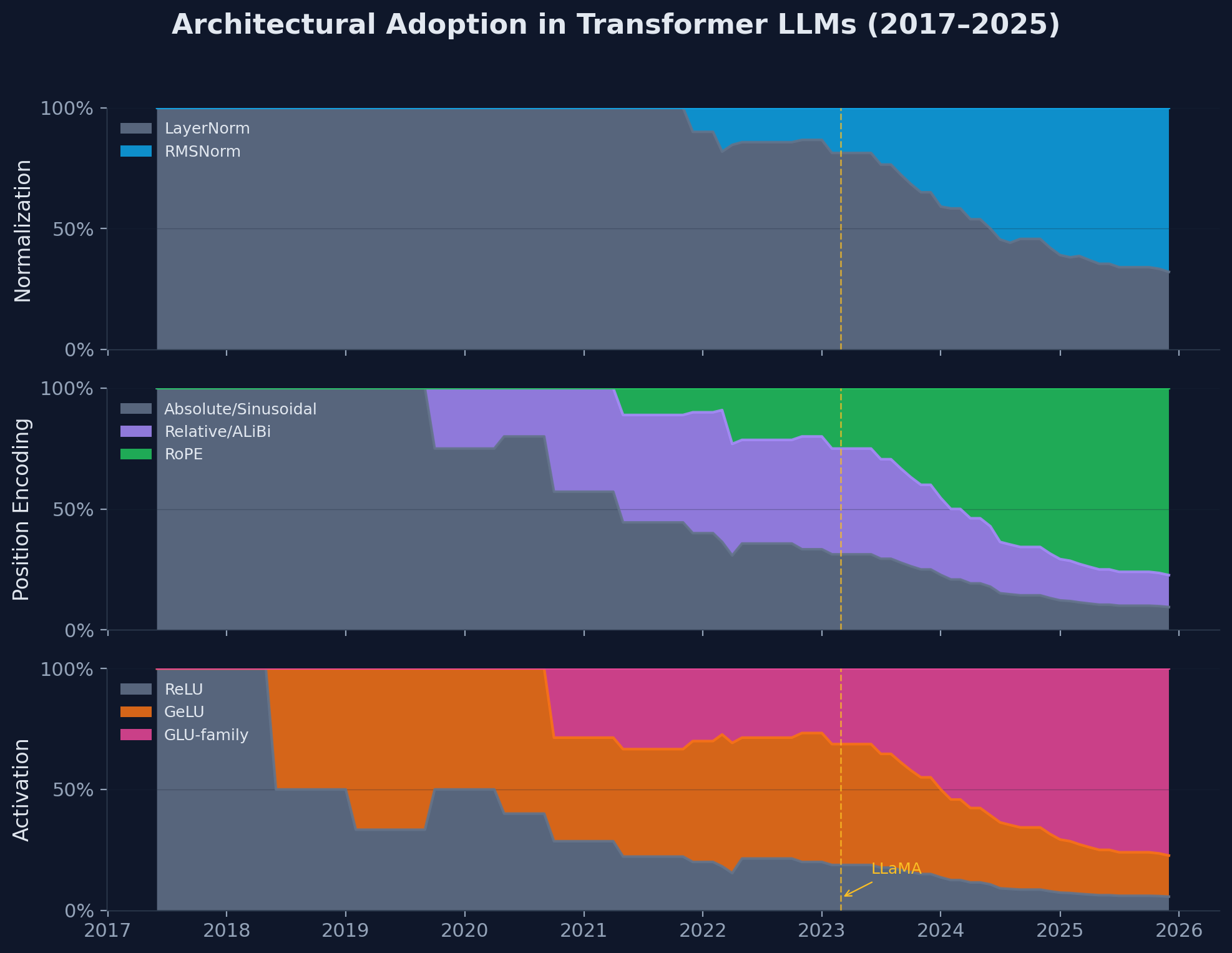

Between 2017 and 2025, transformer architectures for LLMs underwent rapid exploration followed by striking convergence. This article traces decisions across 53 models and identifies a de facto 2023–2025 stack: pre-norm (RMSNorm), RoPE, SwiGLU MLPs, KV-sharing (MQA/GQA), and bias-free layers. We discuss both model-intrinsic factors (optimization stability, quality-per-FLOP) and practical constraints (kernel availability, KV-cache economics). Diversity persists mainly in MoE routing and long-context attention. The accompanying dataset records publication dates and architectural specs.

In June 2017, [4] introduced the transformer with a specific set of architectural choices: post-layer normalization, sinusoidal position encodings, ReLU activations, and 4x MLP expansion. Each choice was reasonable but not obviously optimal. The subsequent eight years saw extensive experimentation with alternatives.

By 2024, many influential open-weight decoder-only model families converged on a similar bundle: pre-norm (often RMSNorm), RoPE-family position encodings, GLU-family MLPs (commonly SwiGLU with parameter-matched width), and KV-sharing attention variants (MQA/GQA). Several also drop most bias terms (sometimes keeping QKV-only biases). This is not literally universal, as there are notable hybrids and counter-trends (e.g., ALiBi/relative-bias lineages, RoPE+NoPE mixtures, and nonstandard norm stacks), but the center of mass is clear. The original transformer's choices were replaced wholesale.

When many independent groups converge on similar design choices, it is evidence of a strong shared basin of solutions. But convergence can also reflect common constraints (hardware/software stacks, kernel availability, inference economics) and path dependence (influential released checkpoints and reference implementations). The goal here is to separate what appears robust from what may be contingent.

This article examines the architectural evolution through three lenses:

Historical progression: How did we get from the 2017 transformer to the 2025 consensus? What problems did each innovation solve?

Technical foundations: What mathematical properties make RoPE more attractive to learned absolute positions? Why does SwiGLU outperform GeLU despite having fewer effective parameters? Why does QK-normalization stabilize training?

Remaining frontiers: Where has convergence not occurred? What does ongoing architectural diversity in MoE configurations, attention patterns, and stability mechanisms tell us about unsolved problems?

Scope note: "convergence" here is primarily about dense, decoder-only LLM blocks (norm/pos-enc/MLP/attention) rather than training recipe, data, post-training, or system-level inference tricks. The dataset is "widely discussed models", which tilts toward models with public technical reports and/or open weights.

The analysis draws on a dataset of 53 transformer LLMs spanning 2017-2025, with architectural specifications cross-referenced against primary sources.

The evolution of transformer LLMs divides naturally into four eras, each characterized by distinct architectural priorities and innovations.

The original transformer established the fundamental structure that persists today: alternating multi-head self-attention and position-wise feed-forward layers, connected by residual streams. The specific implementation choices, however, were largely inherited from prior work or chosen for simplicity.

Normalization placement followed the convention from residual networks: apply normalization after the residual addition (post-norm). For a sublayer function (attention or FFN), the computation was:

Position encoding used fixed sinusoidal functions, encoding absolute position in dimension as:

This choice was elegant, requiring no learned parameters and theoretically enabling length generalization through the linear properties of sinusoids, but subsequent work showed learned absolute positions performed better in practice.

Feed-forward networks used the standard MLP structure with ReLU activation and 4x expansion:

where and .

GPT-1 (2018) moved to decoder-only architecture with learned absolute positions and GeLU activation. GPT-2 (2019) introduced the critical shift to pre-normalization:

This change is widely associated with improved optimization stability at depth. One intuition is gradient flow: in post-norm, gradients repeatedly pass through normalization in the main residual pathway; in pre-norm, the residual stream provides a cleaner identity path while normalization shapes only the sublayer contribution.

The GPT-3 moment demonstrated that scaling (simply training larger models on more data) produced qualitative capability improvements. This era focused on enabling efficient scaling through architectural refinements.

RMSNorm (Root Mean Square Layer Normalization), introduced by Zhang & Sennrich (2019), gained traction in this period when it was adopted by Gopher and Chinchilla. Standard LayerNorm computes:

where and are the mean and standard deviation across features. RMSNorm simplifies this by removing the mean-centering:

The computational savings are modest (often reported around 10-15%, implementation-dependent), but empirically RMSNorm matches LayerNorm in many transformer settings while simplifying the normalization operation. Mean-centering is not "wrong" per se, but it often appears unnecessary for good training dynamics in modern pre-norm transformers, and removing it can slightly improve efficiency.

Parallel attention and FFN was introduced by GPT-J, GPT-NeoX, and later PaLM. Instead of sequential computation:

the parallel formulation computes both sublayers from the same input and sums:

This can improve hardware utilization by increasing parallelizable work; reported speedups vary by implementation, model shape, and kernel support, but are often on the order of ~10-20% with minimal quality impact.

Rotary Position Embeddings (RoPE) were introduced by Su et al. (2024) and quickly adopted by GPT-J, GPT-NeoX, and PaLM. We defer detailed analysis to Section 3.1, but the key innovation is encoding relative position information through rotation matrices applied to query and key vectors, rather than adding absolute position embeddings to the input.

SwiGLU activation was introduced by Shazeer (2020) and later adopted at scale by PaLM. The technique builds on the Gated Linear Unit family. The standard FFN:

becomes:

where SiLU (Swish) is and denotes element-wise multiplication. The gating mechanism () modulates the activated representation, improving expressivity. However, the third weight matrix increases parameters, so the hidden dimension is reduced from to to maintain parameter count.

LLaMA (February 2023) crystallized the modern architecture. While each component existed before, LLaMA's combination (and Meta's decision to release weights) established a reproducible baseline that virtually all subsequent open models adopted.

The LLaMA recipe is as such:

This recipe succeeded because it simultaneously optimized multiple objectives: training stability, inference efficiency, implementation simplicity, and model quality. The absence of bias terms, for instance, slightly improves training dynamics and simplifies the implementation without measurable quality loss.

Grouped-Query Attention (GQA) addressed the inference bottleneck. In standard multi-head attention (MHA), each head maintains separate key and value projections. For a model with heads, this means separate KV pairs must be cached during autoregressive generation. GQA groups multiple query heads to share single key-value heads:

where (typically or ). This reduces KV-cache memory by the grouping factor with minimal quality degradation, enabling longer contexts and larger batch sizes at inference.

Vocabulary expansion accelerated during this era. LLaMA used 32K tokens, LLaMA 2 maintained this. LLaMA 3 expanded to 128K, and Gemma uses 256K. Larger vocabularies improve tokenization efficiency (fewer tokens per word, especially for non-English languages and code) at the cost of larger embedding matrices. The trend reflects both improved tokenizer algorithms (BPE variants, BBPE) and recognition that embedding parameters are relatively cheap compared to transformer layers.

Stability mechanisms emerged as models scaled:

Logit soft-capping (Gemma 2): Bounds attention logits before softmax to prevent numerical overflow: for cap value .

QK-normalization (Gemma 3, OLMo 2, Qwen 3): Applies normalization to query and key vectors before computing attention scores. We analyze the mathematical motivation in Section 3.4.

Embedding LayerNorm (BLOOM): Normalizes embeddings before the first transformer layer, addressing initialization-related instabilities.

Dense scaling, or simply increasing model parameters, encounters diminishing returns. Training compute scales linearly with parameters, but quality improvements become sublinear. Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) provides a different scaling axis: increase total parameters while keeping active (per-token) parameters constant.

Mixtral 8×7B (January 2024) demonstrated that open MoE models could match dense models of much larger active parameter count. The architecture replaces each FFN with a routed mixture:

where are expert networks (typically standard FFNs), are routing weights from a learned router, and is the number of active experts per token (typically 1-2 for Mixtral, up to 8 for later models).

The expert scaling trajectory over 2024-2025 is dramatic:

| Model | Date | Total Params | Active Params | Experts | Active |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixtral 8×7B | Jan 2024 | 46.7B | 12.9B | 8 | 2 |

| DeepSeek V3 | Dec 2024 | 671B | 37B | 256+1 | 8 |

| Llama 4 Maverick | Apr 2025 | 400B | 17B | 128+1 | varies |

| Kimi K2 | Jul 2025 | 1.04T | 32B | 384 | 8 |

Auxiliary-loss-free load balancing (DeepSeek V3) solved a persistent MoE training problem. Traditional approaches add an auxiliary loss to encourage balanced expert utilization:

where is the fraction of tokens routed to expert and is the average routing probability for expert . This loss encourages balance but distorts the primary training objective.

DeepSeek's innovation introduces a bias term used for selection (to maintain load balance) but excluded from the mixture weights used to form the output. Concretely, experts are selected by , but the output weights are computed from the unbiased router scores over the selected set (formalized below in Section 3.3).

Shared experts (DeepSeek, Trinity, Llama 4) designate one or more experts as always-active, providing a stable baseline that all tokens access. This improves training stability and ensures common knowledge isn't fragmented across specialized experts.

Multi-head Latent Attention (MLA) (DeepSeek V3, Kimi K2) addresses the MoE memory challenge. With hundreds of experts, KV-cache becomes prohibitive. MLA compresses the KV representation through learned down-projections:

where projects to a low-dimensional latent space, and reconstruct keys and values. This dramatically reduces cache memory while preserving attention expressivity.

Architectural convergence cannot be understood in isolation from hardware constraints. Several "winning" choices align closely with GPU/TPU optimization opportunities:

FlashAttention [5] made attention practical for longer sequences by restructuring memory access patterns. This reduced the urgency of linear attention research and made long-context training cheaper, increasing the value of position schemes (including RoPE) that behave well under extrapolation. RoPE is also implementation-friendly: its per-position rotations compose cleanly with common fused-attention kernels.

Tensor core tile sizes (16×16 on A100, 8×8 on H100 for FP8) favor hidden dimensions and head counts that are multiples of these values. The near-universal choice of reflects this constraint as much as any quality consideration.

Memory bandwidth bottlenecks during autoregressive inference push toward KV-cache reduction (MQA/GQA) independently of training quality. A technique that is neutral during training but reduces inference memory by 4-8× will be adopted even if it slightly hurts perplexity.

Fused kernel availability creates path dependence: once FlashAttention, fused RMSNorm, and fused SwiGLU kernels exist and are well-optimized, switching to alternatives incurs engineering cost beyond any quality trade-off. The LLaMA recipe's dominance is partly a network effect - it's what the kernels support best.

This hardware-architecture coupling means that "convergence" partly reflects what is fast on current accelerators, not only what is best in an abstract sense. A different hardware landscape (e.g., higher memory bandwidth, different tile sizes) might favor different architectural choices.

Rotary Position Embeddings (RoPE) have become the dominant default for position encoding in modern LLMs. Understanding why requires examining how position information enters the attention computation.

In standard attention, the relevance of position to position is determined by the dot product . For positions to influence attention, position information must be embedded in and .

Absolute position embeddings add a position vector to the input:

The dot product expands to four terms mixing content and position:

Absolute embeddings can learn relative patterns (GPT-2 and GPT-3 demonstrated this empirically) but the architecture must learn to extract relative information from the interaction of absolute positions. RoPE instead provides a direct inductive bias: relative position enters via a simple algebraic identity, requiring no learning to achieve relative sensitivity. This also interacts favorably with length extrapolation techniques.

RoPE's insight is to encode position through rotation. For a 2D subspace of the query/key vectors, apply a rotation by angle :

The dot product becomes:

Because (rotation matrices compose additively in angle), the attention score depends only on the relative position , not the absolute positions. This is exactly the inductive bias we want.

For the full model dimension , RoPE applies independent rotations to pairs of dimensions, each with a different frequency :

The multi-frequency design encodes relative position at multiple scales, analogous to the original sinusoidal encoding but applied multiplicatively through rotation rather than additively.

RoPE became dominant because it gives a clean relative-position inductive bias without learned position parameters, integrates naturally into existing attention implementations, and tends to behave well in long-context regimes, especially when paired with explicit extrapolation strategies (e.g., NTK-aware scaling, YaRN) and careful training. This is best read as a strong default under modern constraints, not a proof of strict superiority over all alternatives in all regimes. The 2025 models experimenting with "NoPE" (no position encoding) in some layers, combined with RoPE in others, suggest the field is learning that different layers may benefit from different position treatments.

The Gated Linear Unit (GLU) family improves FFN expressivity through multiplicative gating. SwiGLU specifically uses SiLU (Swish) as the activation:

where and is the sigmoid function.

To understand why gating helps, consider what each component contributes:

The gating mechanism allows the network to learn which features of the nonlinear transformation should be amplified or suppressed, conditioned on the input. This is more expressive than applying a fixed nonlinearity.

SwiGLU has three weight matrices () versus two for standard FFN (). To maintain equivalent parameter count with expansion factor :

Standard FFN: parameters

SwiGLU with expansion : parameters

Setting these equal: . For , we get .

The key hypothesis is that gating is worth more than width: trading hidden dimension for a gating mechanism improves expressivity more than the raw capacity lost. Empirically, this hypothesis is supported - SwiGLU consistently outperforms parameter-matched GeLU baselines in controlled comparisons [3]. The gating mechanism's input-dependent modulation allows the network to selectively amplify or suppress features, a form of dynamic computation that static nonlinearities cannot express.

SiLU also has favorable gradient flow properties. Unlike ReLU, it's smooth everywhere and has nonzero gradients for all . In practice, SiLU/Swish often behaves comparably to GeLU while pairing naturally with GLU-style gating. The derivative:

is nonzero over a wide range (unlike ReLU's hard zero on ), which can improve gradient flow in practice; empirically, GLU-family MLPs often deliver better quality at similar parameter/FLOP budgets in transformer LMs.

Mixture-of-Experts architectures must solve a fundamental tension: tokens should be routed to the experts best suited for them, but all experts should be utilized to justify their parameter cost.

But MoE is prone to routing collapse. Without intervention, MoE training often converges to using only a few experts. Once an expert becomes slightly better for some token types, it receives more training signal, improving further, creating a feedback loop that starves other experts.

Traditionally, a load-balancing auxiliary loss is added:

where and .

This encourages the router to spread probability mass and actual routing decisions evenly. The problem: it distorts the primary language modeling objective. The router is incentivized to balance load even when some experts are genuinely better for certain tokens.

DeepSeek's auxiliary-loss-free approach introduces a bias term for each expert that affects routing decisions but not expert weighting:

Experts are selected by taking the top- scores under (the biased routing scores), but mixture weights are computed from the unbiased over the selected set.

The biases are adjusted during training to maintain load balance (increase for underutilized experts), but because they don't affect the actual weighting, the model's output is determined purely by learned routing quality.

This is elegant: routing decisions include the bias (ensuring balance), but output computation excludes it (preserving training signal fidelity).

Query-key normalization has emerged as a critical stability mechanism for large-scale training. The mathematical motivation stems from the statistics of high-dimensional dot products.

For query and key vectors with independent, zero-mean entries of variance , and assuming and are independent of each other, the dot product has variance:

These assumptions approximately hold at initialization but break down during training: entries become correlated, means drift from zero, and - independence fails since both derive from the same input. The practical concern is not the initialization variance but drift - the learned norms of and can grow during training, increasing logit magnitudes and sharpening softmax distributions in ways the scaling cannot prevent.

Even when is held constant, the learned norms of and can drift during training, increasing logit magnitudes and sharpening the softmax. This creates two problems:

The standard mitigation is the scaling in attention:

This scaling normalizes the dot-product variance under idealized assumptions (e.g., independent entries with fixed variance), but in trained models the norms and distributions of and can drift with depth, scale, and optimization, producing occasional logit blow-ups and overly peaky attention.

QK-normalization directly controls the vector norms:

With strict L2-normalization and fixed scaling, the dot product is bounded , which can prevent extreme logits. In practice, many implementations use RMSNorm-style normalization and may include learnable scales, so the benefit is better understood as controlling norm drift and reducing pathological logit growth, not as an absolute bound in all configurations.

The practical implementation often uses RMSNorm rather than L2 normalization, and may include learnable scale factors:

Models using QK-norm (Gemma 3, OLMo 2, Qwen 3, Kimi K2, Trinity) report more stable training, especially at scale. The technique appears most beneficial for:

The accompanying dataset documents architectural specifications for 53 transformer LLMs from June 2017 through December 2025. All entries were cross-referenced against public sources, with undisclosed information marked.

A note on interpretation: this dataset is descriptive, not a controlled ablation study. Reported frequencies summarize what was adopted, but adoption reflects a mix of model quality, training stability, inference economics, and ecosystem path dependence (e.g., widely copied open baselines). We also note the following limitations:

Normalization convergence:

Position encoding evolution:

Activation functions:

MoE adoption:

Attention variant:

Block structure:

Vocabulary size trends:

| Model | Date | Norm | Position | Activation | Attn | Block | MoE | Vocab | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Transformer | 2017-06 | Post LayerNorm | Sinusoidal | ReLU | MHA | Serial | No | 37K | None |

| GPT-1 | 2018-06 | Post LayerNorm | Learned Abs | GeLU | MHA | Serial | No | 40K | None |

| GPT-2 | 2019-02 | Pre LayerNorm | Learned Abs | GeLU | MHA | Serial | No | 50K | Modified init |

| T5 | 2019-10 | Pre LayerNorm | Relative | ReLU | MHA | Serial | No | 32K | None |

| GPT-3 | 2020-05 | Pre LayerNorm | Learned Abs | GeLU | MHA | Serial | No | 50K | Modified init; sparse attn |

| T5 v1.1 | 2020-10 | Pre LayerNorm | Relative | GeGLU | MHA | Serial | No | 32K | None |

| mT5 | 2020-10 | Pre LayerNorm | Relative | GeGLU | MHA | Serial | No | 250K | None |

| GPT-J | 2021-05 | Pre LayerNorm | RoPE | GeLU | MHA | Parallel | No | 50K | None |

| LaMDA | 2021-05 | Pre LayerNorm | Relative | Gated-GeLU | MHA | Serial | No | 32K | None |

| Gopher | 2021-12 | Pre RMSNorm | Relative | GeLU | MHA | Serial | No | 32K | Low LR; grad clip |

| Chinchilla | 2022-03 | Pre RMSNorm | Relative | GeLU | MHA | Serial | No | 32K | None |

| GPT-NeoX | 2022-04 | Pre LayerNorm | RoPE | GeLU | MHA | Parallel | No | 50K | None |

| PaLM | 2022-04 | Pre LayerNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | MHA | Parallel | No | 256K | No biases; shared emb |

| OPT | 2022-05 | Pre LayerNorm | Learned Abs | ReLU | MHA | Serial | No | 50K | Modified init |

| BLOOM | 2022-11 | Pre LayerNorm | ALiBi | GeLU | MHA | Serial | No | 251K | Embedding LayerNorm |

| LLaMA | 2023-02 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | MHA | Serial | No | 32K | No biases |

| LLaMA 2 | 2023-07 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 32K | No biases |

| Qwen | 2023-09 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | MHA | Serial | No | 152K | None |

| Mistral 7B | 2023-10 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 32K | Sliding window |

| Yi | 2023-11 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 64K | None |

| DeepSeek | 2024-01 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 102K | None |

| Mixtral | 2024-01 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | 8E/2act | 32K | Load balance loss |

| OLMo | 2024-02 | Pre LayerNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | MHA | Serial | No | 50K | No biases |

| Gemma | 2024-02 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | GeGLU | MHA | Serial | No | 256K | None |

| Phi-3 | 2024-04 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | GeGLU | MHA | Serial | No | 100K | Blocksparse attn |

| Reka Flash | 2024-04 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 100K | None |

| Nemotron-4 | 2024-06 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 256K | None |

| GLM-4 | 2024-06 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | MHA | Serial | No | 150K | No bias except QKV |

| Qwen 2 | 2024-07 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE+DCA | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 152K | QKV bias |

| LLaMA 3 70B | 2024-07 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 128K | None |

| LLaMA 3 405B | 2024-07 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 128K | None |

| Mistral Large 2 | 2024-07 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 32K | - |

| Falcon 2 | 2024-07 | Pre LayerNorm | RoPE | GeLU | MHA | Parallel | No | 65K | FlashAttention-2 |

| Gemma 2 | 2024-08 | Pre+Post RMSNorm | RoPE | GeGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 256K | Logit cap; local/global |

| Command R+ | 2024-09 | Pre LayerNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 256K | RAG opt |

| Qwen 2.5 | 2024-12 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 152K | QKV bias |

| Phi-4 | 2024-12 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | GeGLU | MHA | Serial | No | 100K | Synthetic data |

| DeepSeek V3 | 2024-12 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | MLA | Serial | 256E+1/8act | 128K | Aux-free; FP8 |

| OLMo 2 | 2025-01 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | MHA | Serial | No | 100K | QK-Norm; Z-Loss |

| MiniMax M2 | 2025-01 | DeepNorm+RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | MHA | Serial | 32E/2act | 200K | Lightning Attention |

| DeepSeek R1 | 2025-01 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | MLA | Serial | 256E+1/8act | 128K | Aux-free; FP8 |

| SmolLM2 | 2025-02 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | MHA | Serial | No | 49K | Embedding tying |

| Gemma 3 | 2025-03 | Pre+Post RMSNorm | RoPE | GeGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 262K | QK-norm; 5:1 local/global |

| Command A | 2025-03 | Pre LayerNorm | RoPE+NoPE | SwiGLU | MHA | Parallel | No | 255K | No biases; FP32 ops |

| Llama 4 Scout | 2025-04 | Pre RMSNorm | iRoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | 16E+1/var | 202K | MetaP init; FP8 |

| Llama 4 Maverick | 2025-04 | Pre RMSNorm | iRoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | 128E+1/var | 202K | MetaP init; FP8; fusion |

| Qwen 3 | 2025-05 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 152K | QK-Norm; no QKV bias |

| Mistral Medium 3 | 2025-05 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | No | 131K | - |

| GLM-4.5 | 2025-07 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | 64E/4act | 150K | QK-Norm; Muon |

| Kimi K2 | 2025-07 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | MLA | Serial | 384E/8act | 130K | QK-Clip; MuonClip |

| INTELLECT-3 | 2025-11 | Pre RMSNorm | RoPE | SwiGLU | GQA | Serial | 64E/4act | 150K | Same as GLM-4.5-Air |

| Trinity Nano | 2025-12 | Depth-scaled RMSNorm | RoPE+NoPE | SwiGLU+Gated | GQA | Serial | 128E/8act | 32K | QK-norm; sigmoid route |

| Trinity Mini | 2025-12 | Depth-scaled RMSNorm | RoPE+NoPE | SwiGLU+Gated | GQA | Serial | 128E+1/8act | 32K | QK-norm; sigmoid route |

LLaMA's February 2023 release marks a clear architectural boundary. Before: significant diversity in normalization, position encoding, and activation choices. After: near-universal adoption of the LLaMA recipe.

MoE configuration diversity persists. Unlike the converged dense architecture, MoE models show wide variation:

This diversity suggests MoE design is not yet settled. The optimal configuration likely depends on training budget, target inference cost, and use case.

Stability mechanisms cluster in 2024-2025: QK-normalization, logit capping, and specialized initialization appear almost exclusively in models from the last 18 months. This reflects both scaling to larger models where stability matters more and accumulated understanding of failure modes.

A reasonable reading of 2017–2025 is not that architecture is "done", but that dense decoder-only transformers have a highly competitive default configuration under modern constraints (training stability, throughput on current accelerators, and inference KV-cache cost). Concretely:

Default baseline (dense decoder-only). A common starting point is the consensus recipe: pre-norm with RMSNorm, RoPE, SwiGLU (≈8/3 MLP expansion when parameter-matching), and an attention variant that controls KV-cache (MQA/GQA depending on the quality/latency budget). Many successful families also drop most bias terms.

Treat deviations as hypotheses with measurable consequences. When one of these defaults changes, it is usually treated as a hypothesis about what will improve and what will be measured. In practice, architecture changes trade off among:

MoE is where "architecture" still moves quickly. Unlike the converged dense recipe, MoE design remains context-dependent: expert count, active experts per token, shared experts, routing objective, and load balancing all interact with the data mix and training budget. Reported development cycles tend to involve tuning, and common failure modes (routing collapse, instability at scale) are often first-order concerns.

Stability mechanisms are cheap insurance. As scale and context length increase, training can become more brittle. Techniques like QK-normalization / clipping, attention logit soft-capping, and specialized initialization are lightweight relative to the cost of a failed run. Even when they do not move final metrics, they can reduce "training crisis" risk.

Where most gains usually come from. In many published comparisons, the largest deltas come from data, optimization/training recipe, and post-training/alignment (and from inference engineering in deployment-facing settings) more than from swapping core architectural components within the standard transformer block.

Architectural convergence is evidence of a strong shared basin of solutions, but it is not a proof of global optimality. It reflects both model-intrinsic considerations and strong external constraints.

Convergence reflects constraints and ecosystem dynamics. Choices that win often do so because they are good and easy to scale: they are stable at depth, efficient on GPUs/TPUs, compatible with fused kernels, and friendly to inference economics (especially KV-cache). Influential released baselines and reference implementations can accelerate standardization, creating path dependence even when multiple alternatives are viable.

But here's what convergence does not settle:

There is also a monoculture trade-off. A strong default accelerates progress and reproducibility, but it narrows exploration. This is particularly relevant for nonstandard settings (very long context, low-latency streaming, memory-limited deployment), where the best architecture might differ from the mainstream recipe.

Finally, a useful research posture would be to treat the consensus stack as a hard-to-beat baseline, and aim for claims of the form: "under explicit constraints X and evaluation Y, modification Z reliably improves metric M and does not regress N". That standard is what distinguishes robust architectural progress from recipe churn.

Under what regimes does RoPE underperform? RoPE dominates current practice, but ALiBi was designed for length extrapolation and relative-bias approaches may handle certain retrieval patterns better. At what context length, and for what tasks (e.g., retrieval vs. generation), do alternatives outperform RoPE with standard extrapolation (NTK-aware, YaRN)?

Is there a scaling law for expert count? Mixtral uses 8 experts; Kimi K2 uses 384. Both work. We could study whether optimal expert count scales as for training compute , with active experts held constant. What is , and does it depend on data diversity?

What is the quality/efficiency Pareto frontier for subquadratic attention? Linear attention variants underperform softmax at scale, but hybrids (e.g., Lightning Attention) suggest a middle ground. For a fixed compute budget, what mix of linear and softmax layers maximizes quality? Does the optimal ratio change with sequence length?

Is 8/3 expansion optimal, or just conventional? The SwiGLU ratio emerged from parameter-matching, not optimization. We could sweep expansion factors from 2 to 4 at fixed total parameters and measure downstream task performance. Does the optimal ratio vary with model scale?

What would trigger an architectural phase transition? Mamba and state-space models offer complexity but haven't displaced transformers. Hypothesis: the transition requires either (1) a task regime where is prohibitive (million-token contexts with dense attention), or (2) hardware where memory bandwidth dominates compute. Which comes first?

The eight-year trajectory from the original transformer to 2025 frontier systems follows a pattern of exploration → convergence → renewed divergence:

| Era | Period | Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| I | 2017-2019 | Foundations established, immediate variations explored |

| II | 2020-2022 | Scaling drove efficiency innovations (RMSNorm, RoPE, SwiGLU) |

| III | 2023-2024 | LLaMA crystallized a reproducible recipe, standardization accelerated |

| IV | 2024-2025 | MoE emerged as dominant scaling axis, diversity returned |

The dense-model convergence on a core bundle (pre-norm + RMSNorm + RoPE + SwiGLU, often paired with MQA/GQA-style KV sharing and reduced bias usage) suggests a robust, highly competitive basin of solutions under today’s constraints. It is evidence of what tends to work when optimizing simultaneously for stability, throughput on current accelerators, and inference cost, while also benefiting from an ecosystem of shared implementations and kernels. It is not, by itself, a proof of global optimality.

At the same time, the remaining variation (MoE routing and expert design, long-context attention patterns, and an increasing number of explicit stability interventions) highlights where the architecture is still actively adapting. These choices look less like settled convention and more like responses to new failure modes that appear at larger scale and longer context.

If there is a meta-lesson in the 2017 → 2025 shift, it is how quickly "reasonable defaults" can change once scale and constraints change. Many early design choices (post-norm, learned absolute positions, ReLU) were not wrong so much as eventually outcompeted. The next shift may come from long-context regimes, different hardware constraints, or architectures that change the attention/computation trade-off entirely.

This analysis is inspired by Tatsunori Hashimoto's lecture on architectures and hyperparameters in Stanford CS336 (April 2025).